Rose Petal Jelly

From the earliest times, indeed throughout the history of civilization, people from around the world have held the rose close to their hearts.

Earliest roses are known to have flourished 35 million-years ago originating in Asia.The earliest known gardening was the planting of roses along the most traveled routes of early nomadic humans.

In ancient Mesopotamia, Sargon I, King of the Akkadians (2684 BC -- 2630 BC) brought "vines, figs and rose trees" from a military expedition beyond the River Tigris.

Rose petals were used in Ancient Egypt, and petrified rose wreaths have been unearthed from Egyptian tombs of antiquity. During the late Ptolemic period (305 BC–30 BC), Cleopatra had her living quarters filled with the petals of roses so that when Marc Antony met her, he would long remember her for such opulence and be reminded of her every time he smelt a rose. Her scheme worked for him. Such is the power of roses.

The "rosa gallica" was already praised by the Greek poet Anacreon in the 6th century BC.

It was probably brought to Gaul with the Roman conquest. The Romans cultivated a great beauty. Rose petals were also popular in Rome and Greece with the oil produced from them being used as both a medicine and as a perfume for wealthy Romans. The rose petals were used for balms and oils in the Roman society, particularly when worshiping the dead.Roman high society women used petals much like currency believing that they could banish wrinkles if used in poultices. Rose petals were often dropped in wine because it was thought that the essence of rose would stave off drunkenness and victorious armies would return to be showered with rose petals from the civilians that crowded the balconies above the streets long before the confetti and ticker tape parades welcoming events and people of note in New York City in the 20th Century. The Romans also used them as adornments at weddings where they were made into crowns to be worn by the bride and the groom.

And Even though petrified remnants of roses wreaths have been have been found in ancient Egyptian tombs and the evidence of rose hips having been found in Europe, the earliest record of roses being cultivated by the Chinese was about 5,000 years ago.

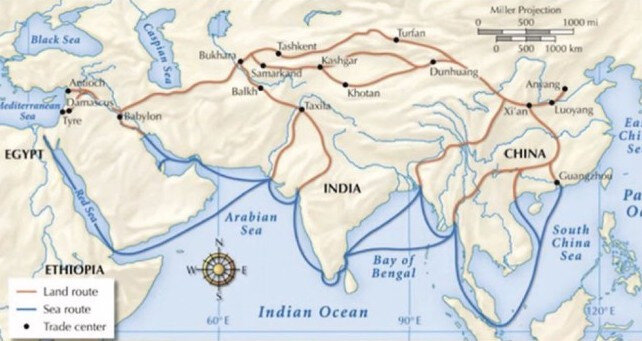

And because of trade and wars, the rose has been popular throughout the Middle East, with Iran being the center of it all. You see, Iran, historically known as Persia, is situated on a bridge of land that connects the Middle East with the Far East. And because of Persia's geographic position, roses have also been a staple in Persian cuisine for over a 3,000 years. It has a considerable place and historical value in the evolution of the culinary arts from the Middle East to Europe, as it was right in the center of the ancient Silk Road.

The Silk Road was an ancient network of trade routes that connected the East and West. and derives its name from the lucrative trade in silk carried out along its length, beginning in the Han Dynasty (207 BC–220 CE). Trade on the Silk Road played a significant role in the development of the civilizations of China, Korea, Japan, the Indian subcontinent, Iran/Persia, Europe, the Horn of Africa and Arabia, opening long-distance political and economic relations between the civilizations. Though silk was the major trade item exported from China, many other goods were traded, as well as religions, syncretic philosophies, and technologies.

Traders in antiquity along the Silk Road in include the Bactrians, Sogdians, Syrians, Jews, Arabs, Iranians, Turkmens, Chinese, Malays, Indians, Somalis, Greeks, Romans, Georgians, and Armenians (Hansen 2012). In addition to economic trade, the Silk Road was a route for cultural trade among the civilizations along its network (Bentley, 1993). And has thus, a transitional point where exchange of cultures and the trade of exotic products and cuisine were passed between the West and the Orient for thousands of years.

Ancient Persians took their wares to all the corners of the world, in particular pomegranates, saffron and spinach, and the country also played host to much of the bargaining between the East and West. These bargained goods, including rice, lemons and eggplant, now feature prominently in the national Iranian dishes were traded for silk and roses. Roses have been used in Persian cuisine for 3,000 years. In fact, the use of rose petals in Middle Eastern cooking is largely the product of Persian influence. Rose petals were adopted throughout the Middle East after the Persian Conquests which established the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC) and subsequently the Sasanian Empire (224–651 AD),and eventually roses were in many cuisines throughout the world including Indian and Chinese food.

Roses often show up in Turkish Delight, a Middle Eastern confection that is one of the oldest sweets in the world. Turkish delight can be made with rose petals or with rose water. They also often show up in certain blends of the Moroccan spice mix known as ras el hanout and in some sweetened rice dishes from India.

In Persian cuisine, dried rose petals have been used in several dishes to flavor or as a garnish. Rose petals are often used to make rose water, which is a less-perishable way to get the rose flavor into baked goods like cakes and puddings. In the Persian household, rosewater is a regular pantry ingredient that is added to sweets, desserts and even coffee.

A popular dessert in modern Iran just happens to be Bastani, a Persian rose and vanilla ice cream desert that is often garnished with cream chunks and sugar coated rose petals (UPDATED 11-14-2021 For the Bastaini Recipe, follow the link to: Food & Wine).

Eventually roses made their way to France. It is said that Thibaud IV, Count of Champagne (1201-1253), He initiated the Barons' Crusade in 1239 and was famous for being a trouvère, and was the first Frenchman to rule Navarre O'Callaghan 1975). According to most historians, the Barons' Crusade was not a glorious campaign, but it did led to several diplomatic successes (Richard, 1999). Souvenirs that he brought back to Europe included a piece of the true cross and the Chardonnay grape which in modern times is an important component of champagne. Thibaud also brought back a rose bush what was named "Provins" (Latin name rosa gallica 'officinalis', the Apothecary's Rose) from this diplomatic expedition to Jerusalem.

Though oral tradition is strong, this is not confirmed by any written chronicle, but the evidence of rose appearing in France during this time, lends credibility to the tale (Fray 2007). Thibaud’s poetic spirit was undoubtedly in awe of the beauty of the rose gardens found in the palaces of the Sultan of Damascus.It is said that Thibaud wanted to cultivate this rose on the hillsides of the Châtel in Provins. One can imagine that, from this intensive cultivation was born the link between the city and the flower, that from then on has been present in the city’s traditions: distinguished visitors, such as Kings Francis Ist, Henri IV, Louis XI, or Queen Catherine de Medicis were offered cushions of dried petals (Evergates, 2007).

Provins always had a vested interest in the cultivation of roses. Over time, these roses have constantly evolved and wild roses started growing next to those cultivated for specific needs (Fray, 2007). This is true of the Rose of Provins, the apothecary rose, first recorded in the 13th century, and was the foundation of

a large industry in growing roses that produced jellies, powders and oils, because this particular rose was believed to cure a multitude of illnesses. , the father of agronomy in France, Olivier de Serres (1539-1619), identified "several virtues to the one who distills rose water used by apothecaries of syrups and other things..." (Hoffman 1984).

His most famous work, the Théatre d'agriculture (1600), provided a complete guide to agricultural practices and helped to outline the ideals of French Protestant culture. Serres advocated agricultural reform, and explained land-management techniques of the utmost importance in an era threatened by nearly continuous famine, drought, and war.

And since medieval times, the rose is still strongly associated with Provins’ confectionery creativity. Provins still produces all sorts of foods from roses, and its main specialties are rose petal jam, fruit jelly, rose honey, rose candy chocolate, liqueur and other delicacies. Provins is also a large producer of wine, with the medieval methods of wine making are still being carried out by residents, and some vineyards are still being used to produce to rose petal wine to this very day (Johnson, 1989).

And whether in France or in the Middle East, rose petal jam made from fresh rose petals often makes an appearance on the breakfast table to be eaten with bread and butter or clotted cream.The sophisticated floral flavor of rose petal jam truly elevates the foodie palette.

And it should be noted that the flavor of rose petals differs depending on which type of rose plant produced them. They can have a floral sweetness or a tartness similar that which comes from citrus fruit. They can also be mildly spicy. They are often intensely aromatic, which is the quality that is most valuable for cooking.

And given the rather long culinary history, how I came to adore rose petal jelly was through my Grand's love of growing her own pink roses, not just for their beauty, but because she loved rose petal jelly too! This is her recipe that I share with you today.

Enjoy!

Ingredients:

4 cups pink or red edible roses* (See Cook's Notes)

6 cups water

1 lemon

6 Tablespoons Class Ball Powdered Pectin **(See Cook's Notes)

3 cups granulated white sugar

Directions:

Measure the petals.Rinse in cold water to remove debris and small bugs, and drain using a colander. Add the petals and the water to a large saucepan . Set the saucepan on the stove and bring it to a boil. Turn the heat down and let the petals simmer for fifteen minutes.

Using a colander lined with a double layer of cheesecloth,pressing all the liquid from the petals strain the liquid into a bowl to cool slightly. Discard the petals.

Measure the liquid. There should be 4 cups. Add additional water to equal 4 cups of rose liquid, if necessary.

Juice one large lemon into the rose water.

Return the liquid to the saucepan, and add the pectin, stirring thoroughly. Place the saucepan back on the stove bring it to a boil, stirring constantly.

Once the liquid is boiling, add 3 the sugar and continue to mixture it boil for an additional two minutes.

Skim any foam that may form ontop of the jelly.

Ladle the jelly into prepared sterilized jars leaving 1/4 inch headspace and cap the jars with the lids and rims. Let the jarred jelly sit to cool and set on the counter overnight.

Jelly can be stored in the refrigerator for up to six months.

To preserve for storage at room temperature, cover jars with lids and rims, place in a hot water bath (2 -3 inches boiling water) for 15 minutes at a hard boil. However, it should be noted that the jelly must be refrigerated after opening.

Serve this versatile accompaniment with scones, crumpets, toast, croissants and other treats. The jelly also has a variety of uses, including using it as a glaze over fruit or tea cakes and even over vanilla ice cream.

Cook's Notes:

*All edible flowers must be free of pesticides. Do not eat flowers from florists, nurseries, or garden centers. In many cases they are treated with pesticides not labeled for food crops.

Dried rose petals are great in herbal tea mixes, too. You can also mix dried rose petals, tiny rose buds and a few cardamom pods with black or green tea leaves for an exotic brew.

Dried rose petals sold in UK supermarkets and online are mostly sourced from Pakistan and are usually of rosa canina variety. They are dark pink or crimson in color. Persian dried roses are pale pink and come from damascene roses. Both are good for food decorating but most Persian cooks prefer dried roses, available from Middle Eastern groceries and online, for use as a spice.

After boiling, you will notice that the water becomes a dingy brown, and the petals will lose their color. Do not fret. When adding the lemon juice, the acid from the lemons, will transform the liquid into a bright pinkish red.

** One 1.75 ounce package of powered pectin can be used a reasonable substitute.

Sources:

"How to use rose petals in cooking". (2017). The Persian Fusion. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

"Provins in the dark". Retrieved June 23, 2018.

Digest, The Reader's (1978). The world's last mysteries. Montréal: Reader's Digest. p. 303. ISBN 089577044X.

Our Rose Garden.:The History of Roses: University of Illinois Extension. (2018). Retrieved July 1, 2018. Retrieves July 1, 2018. https://extension.illinois.edu/roses/history.cfm

Bentley, Jerry (1993). Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 32.

Boulnois, Luce (2005). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books. p. 66. ISBN 962-217-721-2.

Elisseeff, Vadime (2001). The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce. UNESCO Publishing / Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-92-3-103652-1.

Evergates, Theodore (2007). The Aristocracy in the County of Champagne, 1100-1300. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Fray, Jean-Luc (2007). Villes et bourgs de Lorraine: réseaux urbains et centralité au Moyen Âge (in French). Presses Universitaires Blaise-Pascal.

Hansen, Valerie (2012). The Silk Road. OUP US. p. 218. ISBN 9780195159318. Archived from the original, Retrieved June 20, 2017. Jewish merchants have left only a few traces on the Silk Road.

Hoffman, Philip. (1984). "The Economic Theory of Sharecropping in Early Modern France". The Journal of Economic History 1984, page 312.

Johnson, Hugh. (1989). Vintage: The Story of Wine pg 122. Simon and Schuster.

O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (1975). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press.

Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, C.1071-c.1291. Translated by Birrell, Jean. Cambridge University Press.

Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War:A New History of the Crusades. Penguin Books.

Xinru, Liu, (2010). The Silk Road in World History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 11. "Republic of Korea | Silk Road". en.unesco.org. Archived from the original. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

Hello Friends!

All photographs and content, excepted where noted, are copyright protected. Please do not use these photos without prior written permission. If you wish to republish this photograph and all other contents, then we kindly ask that you link back to this site. We are eternally grateful and we appreciate your support of this blog.